Every year, the dry season brings agricultural work in northern Ghana to a grinding halt. People are unable to farm without rainfall, so its absence for a long period of time severely limits their livelihoods.

Wider access to irrigation could reverse that. As a dependable alternative to scarce or variable rainfall, irrigation enables farmers not only to grow crops during the dry season but also to grow more of them all year round. A boost in agricultural productivity generates positive ripple effects through all segments of society, from increasing food security to creating jobs and helping people afford health care and school fees. Sub-Saharan Africa, where 70% of the population is smallholder farmers, is poised to profit from irrigation.

Despite its benefits, however, the success of public irrigation schemes is hindered by many challenges, such as weak institutions, poor site selection, inadequate maintenance and reservoir siltation. Many farmers must invest their own resources to acquire irrigation technologies, which pose financial and technical barriers. The poorest and most marginalized groups are most likely to miss out. As a result, farmer-led irrigation—like public irrigation—runs the risk of advantaging some populations while further marginalizing others.

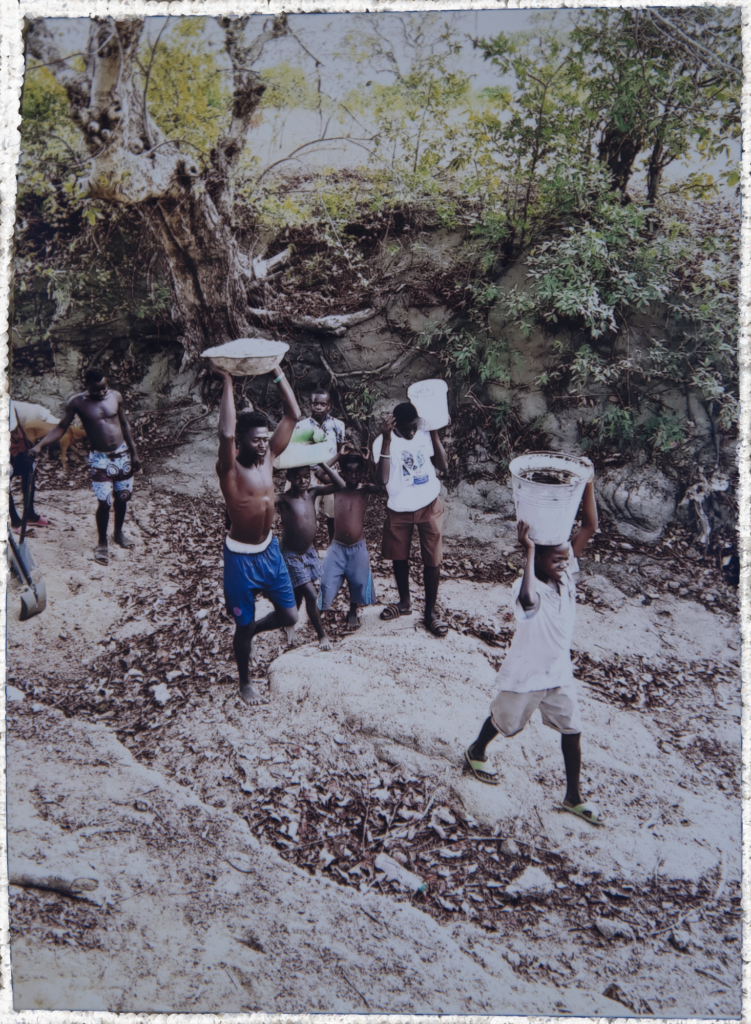

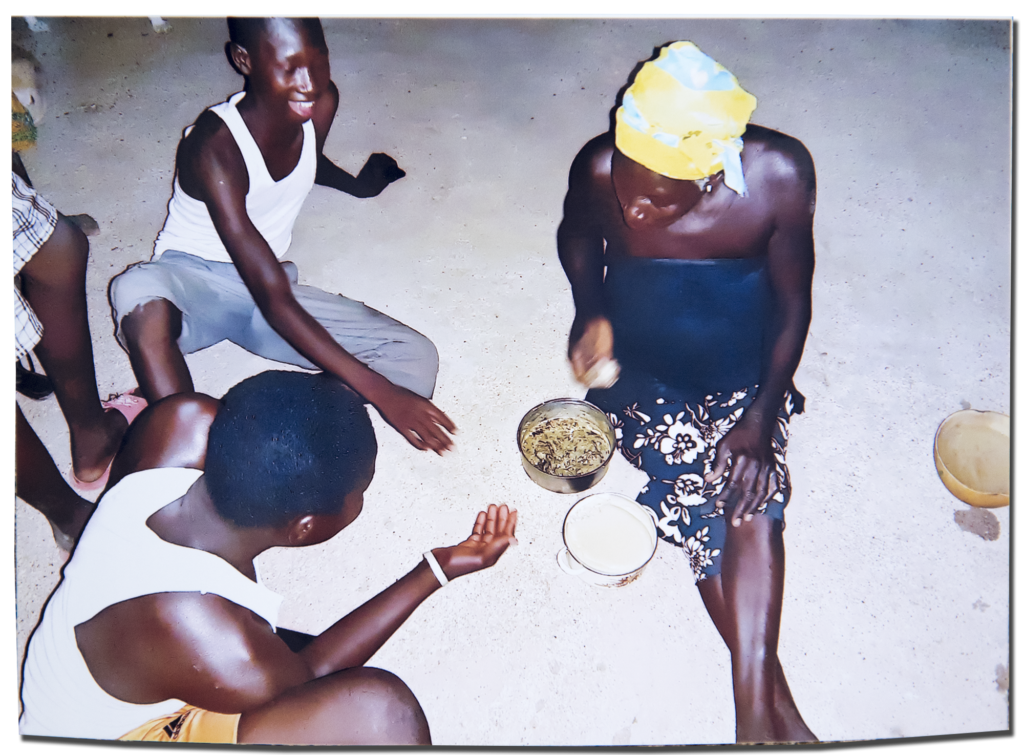

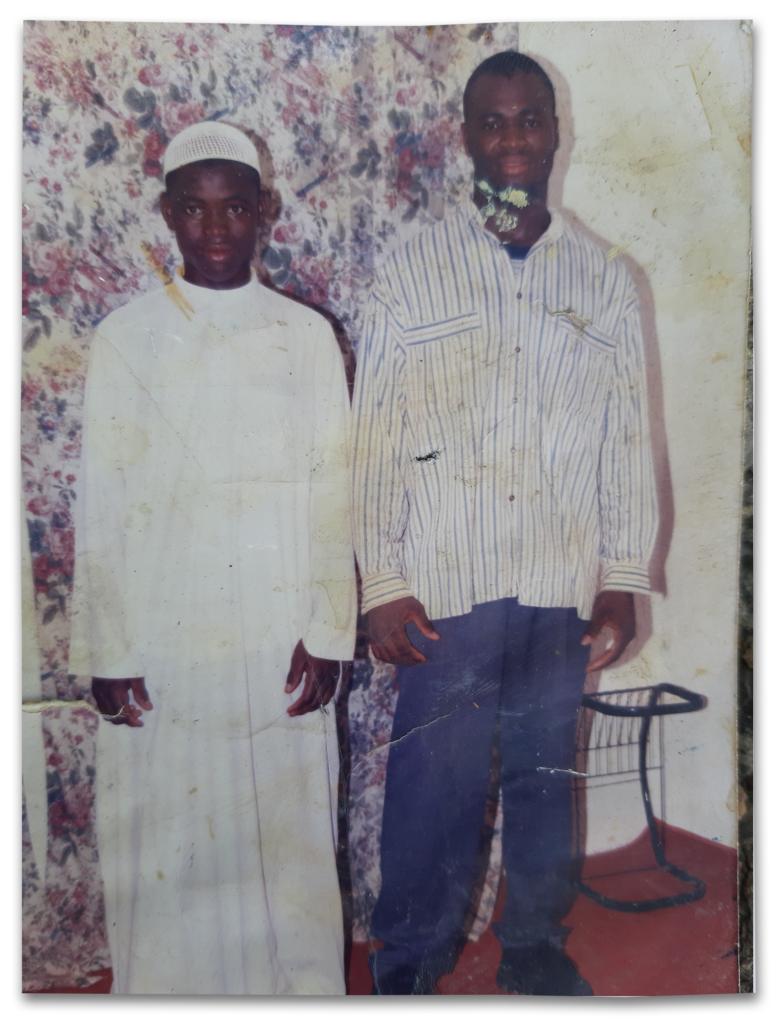

Two young men from the Upper East region of Ghana share their experiences during the dry season. Through photos of daily life, they illustrate how access to irrigation (or the lack thereof) impacts them, along with its potential to change the lives of many others.

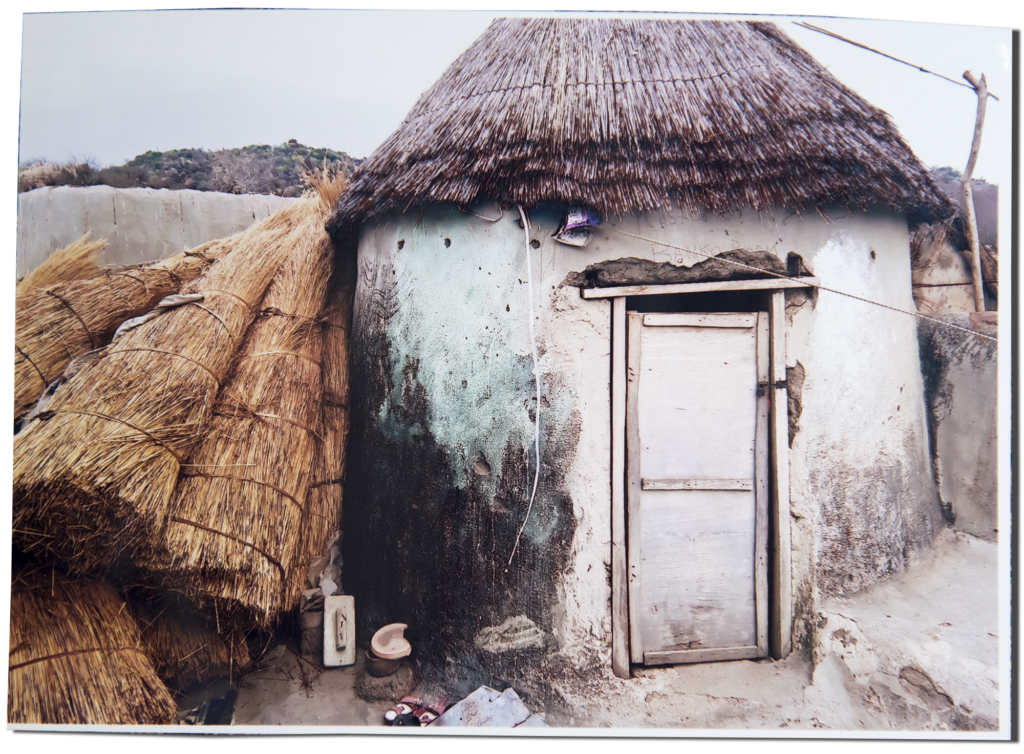

Edward "Paskinny" Tinadoo

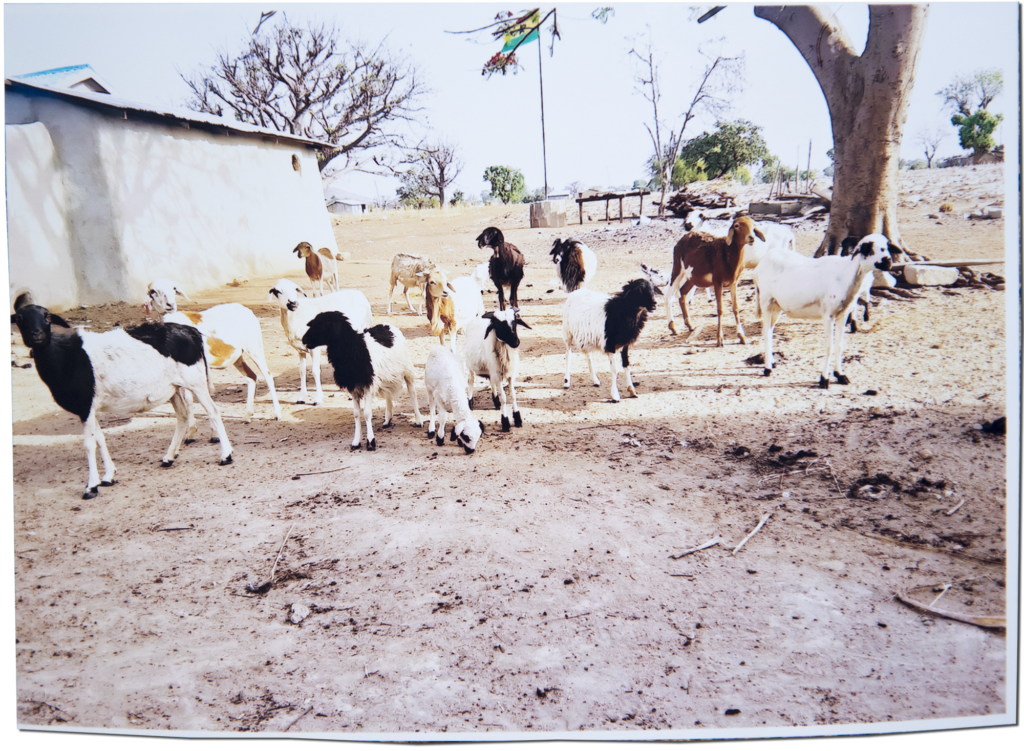

Agriculture also involves rearing animals, such as goats and fowls, chickens and cows. This has really come to help us a lot in our community. When you farm and that season you don’t get a good harvest, you can use the animals you’re rearing to sell and get money for that season. It really helps.

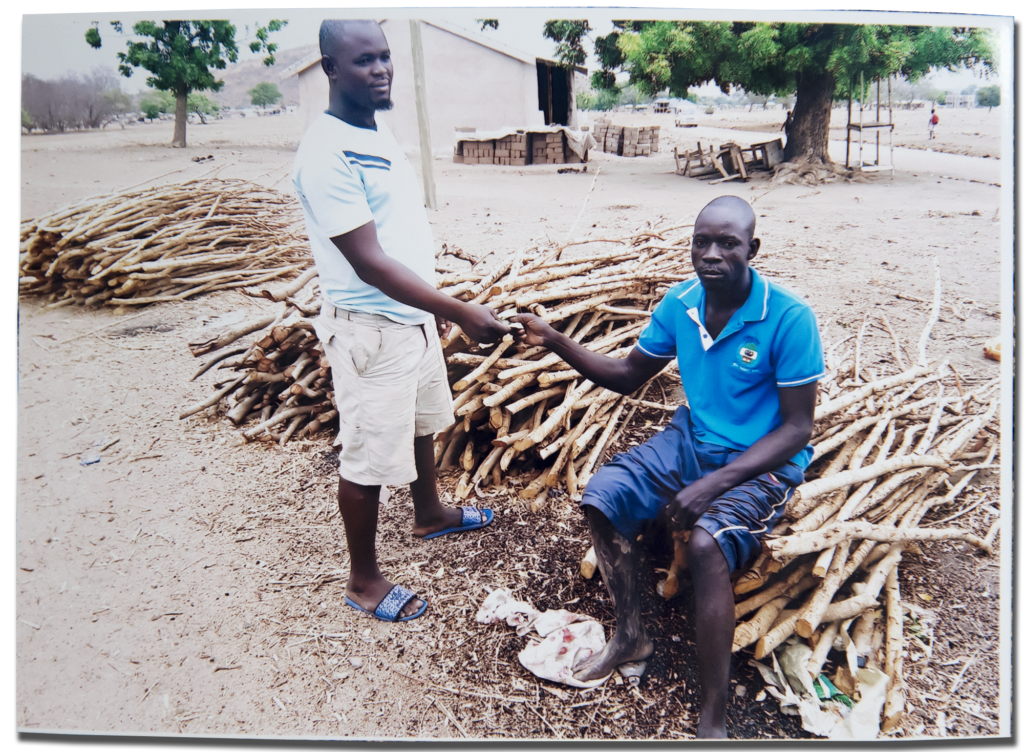

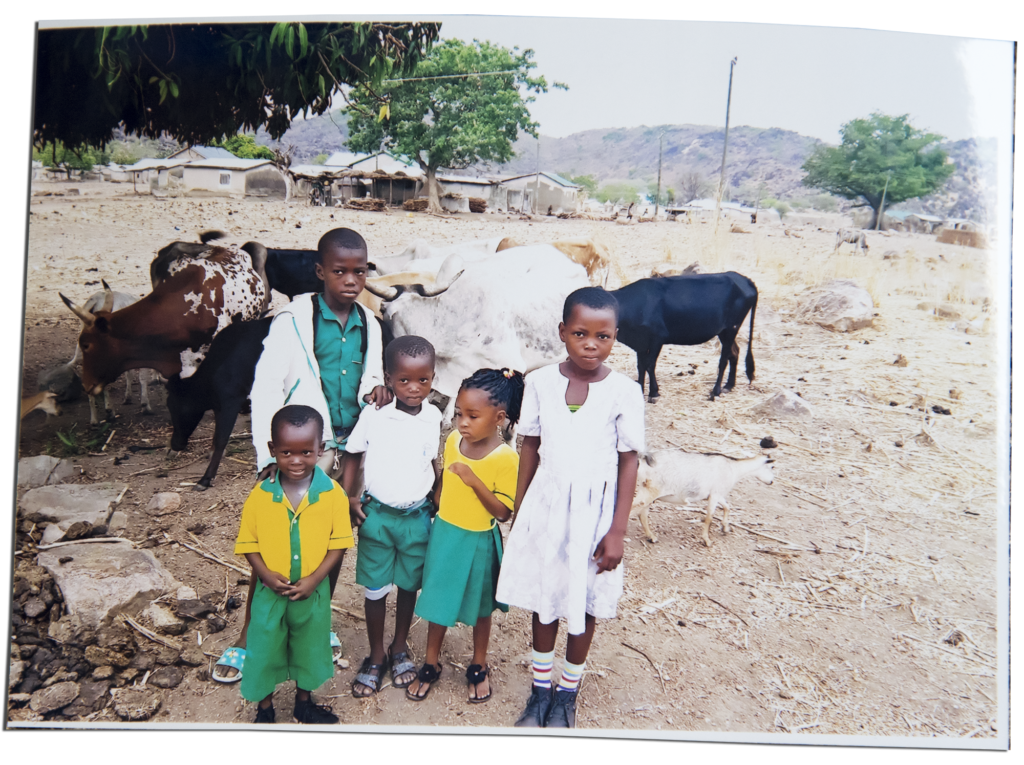

Arrow Bawa "Fifty" Letima

During the three years I worked for him, he never sent money to my parents, much less pay me. I didn’t understand what was going on, but my brother advised me to continue working for him because he promised to let me learn a trade, such as welding, carpentry or driving. As time went on, I realized nothing would ever happen.

It’s my prayer that my cows will be many so I can take care of my kids in case they fall sick or need to pay school fees or anything bad happens to them. My hope for my children is that they should be able to go to school and become prominent people in our society. When they grow up, in case there’s anything concerning writing or English, they should be able to talk for me. They shouldn’t be like me right now. I look forward to them being better than me. When there’s a need for me to use money to solve one of these problems, I’ll sell a cow to solve the problem.

For this reason, I don’t do any major activities during the dry season. So I’m appealing to the authorities to come to my aid by digging a borehole for us to do dry season farming, such as onions, peppers and tomatoes.

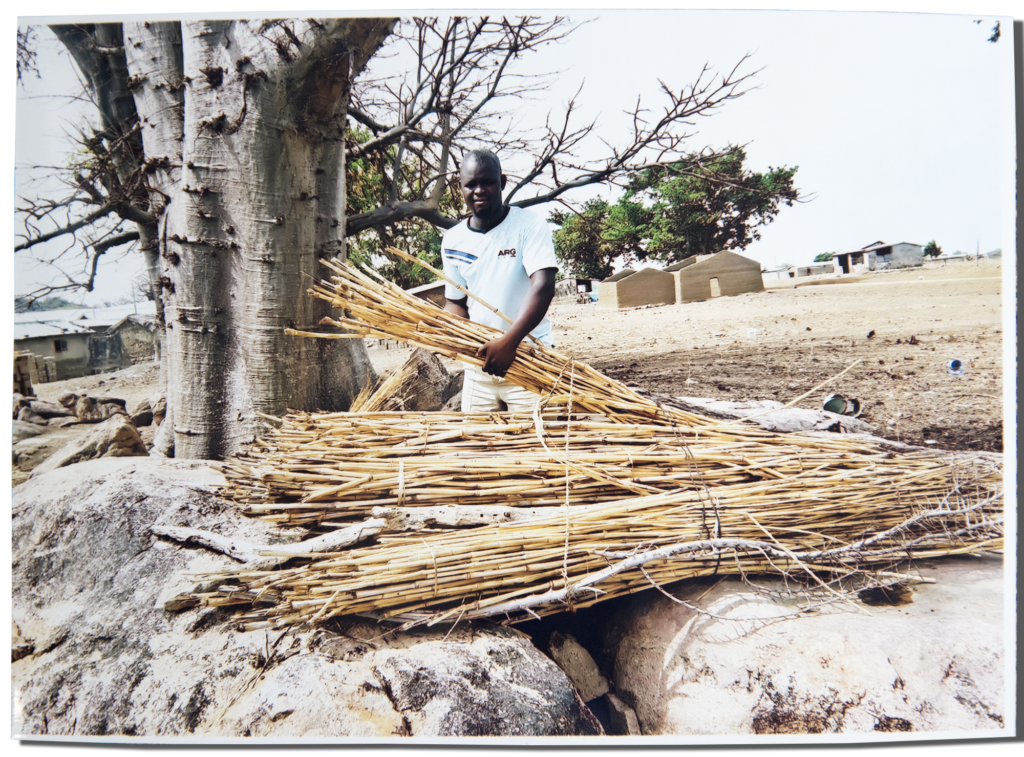

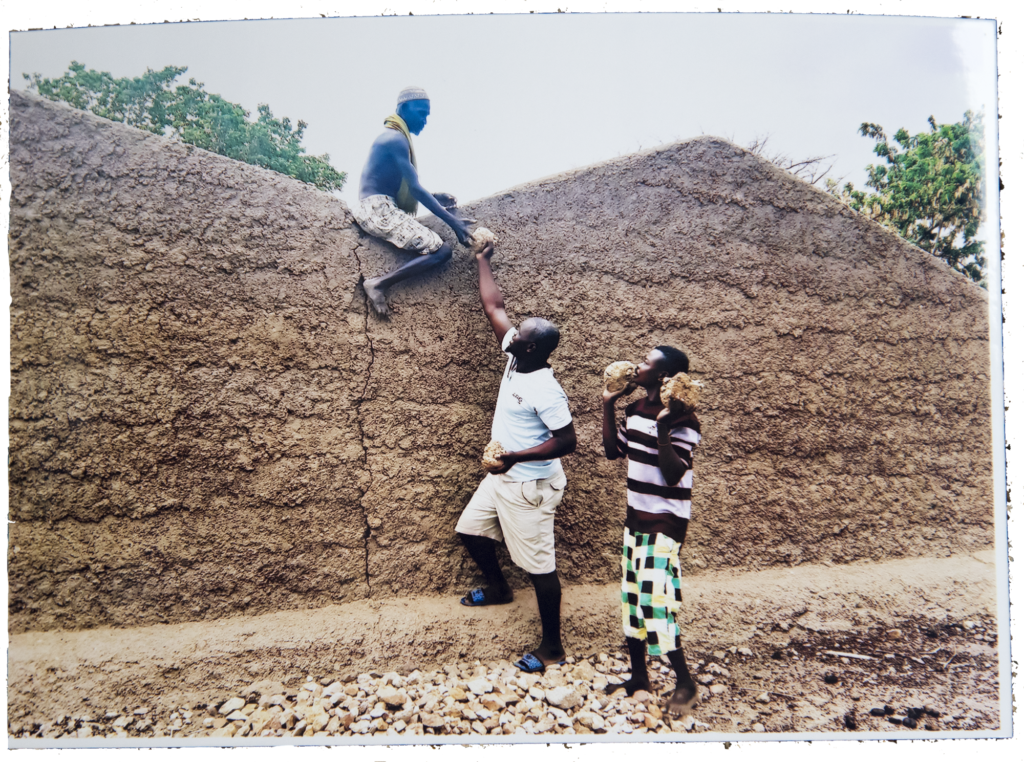

Paskinny and Fifty—neither of whom have access to public irrigation schemes—are both participants in the International Water Management Institute’s project about Bhungroo Irrigation Technology. Farmers in Gorogo and Sepat suffer from not only lack of water during the dry season, but also extensive flooding during the rainy season. With better water management, they could increase their agricultural productivity and climate resilience throughout the year. Bhungroo Irrigation Technology stores excess floodwater underground during the rainy season so it is available for use during the dry season. Once the Bhungroo system has stored water, Paskinny accesses it to irrigate his garden using a solar pump. Solar pumps are promising irrigation technologies for off-grid communities like Gorogo and Sepat because they do not require fuel costs or electricity.

With access to irrigation, Paskinny is able to grow and sell vegetables for a profit, which he uses to purchase food and school supplies for his younger siblings. He hopes to someday expand the irrigated garden in his village, so others can do the same. Without access to irrigation technology, Fifty is unable to farm or generate a consistent income during the dry season, leaving him with limited options if his children fall ill or require financial support.

When it comes to irrigation, "I'm not talking about want," says Luu Yin, the chief of Gorogo. "I'm talking about need."

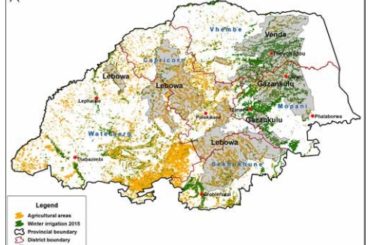

Access to irrigation offers widespread, unequivocal benefits. Millions of smallholder farmers around the world would be better equipped to support their families, which in turn reduces rural poverty and combats chronic hunger within a growing population — instead of struggling to make ends meet until the dry season ends. In Ghana, up to 210,000 hectares are economically and biophysically suitable for irrigation, which could support 690,000 smallholder farmers. The continent of Africa could double its crop yields and gain as much as USD 22 billion per year for 185 million people.

Nevertheless, many farmers are prevented from reaping the benefits of irrigation due to limited resources and lack of technical know-how. Without financial means, a farmer cannot purchase irrigation technology; without a reliable supply chain, they may have trouble finding fuel for their pump; and without the technical expertise to make repairs, a broken pipeline becomes useless. While the farmer-led irrigation revolution has begun, new business models and training opportunities are necessary for ensuring it will come to fruition. For example, a microfinance organization could partner with organizations that specialize in irrigated agriculture to co-develop an economically viable credit product.

The barriers to accessing irrigation disproportionately affect marginalized groups, such as women, youth and people who are uneducated or resource-poor. Because those who most need the benefits of irrigation are those for whom it is most out of reach, irrigation programs must make special efforts to include them to ensure that the farmer-led irrigation revolution leaves no one behind.

RESOURCES

For More Information about Farmer-led Irrigation in Ghana

The unfulfilled promise of farmer-led irrigation (WLE Thrive blog)

"Only farmers who are already well off – typically younger men – are able to invest in and benefit from irrigation technologies. What about women and other less privileged farmers?"

Pinpointing untapped irrigation potential (IWMI)

"Ambitious efforts are underway in Africa to promote the spread of smallholder irrigation."

“Uber for irrigation” and other novel ways to finance a farmer-led revolution in Africa (Agrilinks)

"Across the continent, if you ask smallholders why they have not yet made the switch from unpredictable rainfed cropping to more reliable irrigated production, they most often cite a lack of affordable credit to purchase pumps and other equipment."

Making hazards into opportunities: what to do about too much and too little water in northern Ghana (IWMI)

"The conditions [of too much water for part of the year, not enough during the rest] seem right for introducing techniques developed to capture standing flood water in the rainy season, store it underground, and make it available for crop irrigation and domestic use in the dry season."

Sustainable and equitable growth in farmer-led irrigation in Sub-Saharan Africa: What will it take? (Water Alternatives)

"Small-scale irrigators tend to be younger, male and better-off. Women and resource-poor farmers – the majority of farmers in sub-Saharan Africa – are disadvantaged and often excluded from the numerous benefits to be gained from irrigation."

Assessing land suitability for aquifer storage and recharge in northern Ghana using remote sensing and GIS multi-criteria decision analysis technique (Modeling Earth Systems and Environment)

"Extensive flooding of agricultural lands during the rainy season and lack of water during the 8-month long dry season affect the livelihood of the people in the northern Ghana, a situation that calls for better water management practices."

Business model scenarios and suitability: Smallholder solar pump-based irrigation in Ethiopia (IWMI)

"This report outlines a business model approach to assessing the feasibility and for encouraging investment in smallholder solar pump irrigation."

Opinion: How to keep Africa's boom in solar-powered irrigation from going bust (Devex)

"Solar-powered irrigation pumps are without a doubt one of Africa’s most promising solutions to climate change impacts and chronic hunger."

Effect of climate change on land suitability for surface irrigation and irrigation potential of the shallow groundwater in Ghana (WLE)

"Estimating the potential land resources suitable for irrigation and evaluating the possible impact of climate change on land suitability is essential for planning a sustainable agricultural system."

Adapting aquifer storage and recovery technology to the flood-prone areas of northern Ghana for dry-season irrigation (IWMI)

"The Bhungroo Irrigation Technology (BIT) is a system designed to infiltrate excess ‘standing’ floodwater to be stored underground and abstracted for irrigation during the dry season."

IWMI’s research on Bhungroo Irrigation Technology in the Upper East region of Ghana was conducted in collaboration with the Conservation Alliance, with generous funding from the United States Agency for International Development. It forms part of the CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE), which receives support from the donors of the CGIAR Fund. Thank you to the residents of Gorogo and Sepat — especially Paskinny, Fifty, Gifty, Starboy and Luu Yin — for sharing their experiences. Thanks also to Richmond Richie for his insight and translations.